While fox hunting across the fields of Villanova—a stretch of countryside on the Philadelphia Main Line—in the early 20th century, a young investment banker named Colonel Robert Leaming Montgomery fell from his steed and was knocked out cold. When he regained consciousness, a sweep of rolling hills, old-growth forests, and snaking streams came into focus. Arcadia, he thought. So he bought it.

In 1911, he hired celebrated Gilded Age architect Horace Trumbauer to design a three-story, fifty-room Georgian Revival mansion, framed by flagstone terraces and a carpet-like bowling green. Down the hill, he set up a dairy, with nine Ayrshire cows imported from Scotland, and a broodmare stable, with seven mares and a stallion from Ireland. He named the whole lot Ardrossan, after the Scottish town from which his ancestors had emigrated. For more than a century, the 850-acre idyll served as the family seat of the Montgomery Scott clan of financiers, lawyers, and horsewomen. “Café society,” one set of future in-laws sniffed when their daughter married a Colonel Montgomery descendent. A family friend, the playwright Philip Barry, later immortalized the estate and its saucy, upper-crust inhabitants in his 1930s drawing room comedy, The Philadelphia Story .

A view of the “Big House” facade during the winter.

“As a child growing up there, I couldn’t have told you which direction was north,” when looking across the vast “patchwork of farms, fields, and woods” that made up “the place,” as the family called it, writes the colonel’s great-granddaughter Janny Scott in The Beneficiary: Fortune, Misfortune, and the Story of My Father , recently published by Riverhead Books. Ardrossan was “land and a house to match his ambition.”

And what a joy it was for Scott to grow up there. “I would come home from school, saddle up my pony, and ride a mile and a half without crossing a road,” she tells AD . On “steamy Philadelphia summer days, we’d head to the cold pool: a swimming pool a good quarter of a mile away in the woods, built in the ’20s and fed by a spring. It was surrounded by vegetation and ferns, and the sun would come in over the tops to the trees. I remember it more vividly than anything else.”

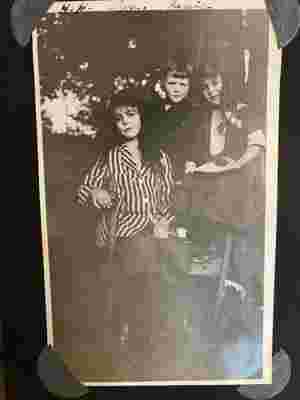

The author’s grandmother, Hope Montgomery Scott (center), with two of her siblings.

In 1969, when Scott was 14, her father, Robert Montgomery Scott, was appointed special assistant to Walter H. Annenberg, U.S. ambassador to Great Britain. The family of five moved to London for four years, Janny leaving Ardrossan, it turned out, for good. She completed her studies in England, and after college, she pursued a career in journalism, much of it at The New York Times . After the diplomatic posting came to an end, her parents returned to their stone farmhouse on Ardrossan, and her father became a local éminence grise, serving as president of Philadelphia’s Academy of Music and Museum of Art. One day, when she was in her twenties, Scott’s father told her he was entrusting his diaries to her—because, he said, “you’re the writer.” Years later, she learned there was an extensive family archive, much of it housed in the ironing room of the Big House, as the mansion was called.

She pushed it to the back of her mind until 2011, following the completion of her first book, A Singular Woman: The Untold Story of Barack Obama’s Mother . “I thought, ‘I have a little time now. Why don’t I go check it out?’” she recalls. “Going through all those letters, telegrams, bills, receipts—they kept everything —was intoxicating. I said to myself, ‘Surely there is a book here.’ I wanted to write about this world that I had been exposed to as a child but had left, and these archives were a way to understand all I didn’t know—how it came about, and who those people really were.”

The ballroom at Ardrossan.

She attacked the subject like a reporter, interviewing relatives and historians, poring over town records and photo albums. She discovered long-hushed secrets—a suicide, love affairs, a tragic young death that reverberated through the family for at least a generation, maybe more. What tied it all together was a collection of grandiose houses that were “completely impractical,” she says.

This cache of real estate included Woodburne, a spread designed by Trumbauer in Landsdowne, Pennsylvania, for her paternal great-grandfather, Edgar T. Scott, an investment banker. It was so humongous that even its chatelaine found it “oversized and pretentious,” Scott writes. There was Chiltern, a “summer palace,” built for the same great-grandfather on the coast of Maine; it was where her father spent every summer until World War II. “I knew nothing about Chiltern until my great-aunt showed me a photo,” she says. “It was wiped off the face of Bar Harbor, because they couldn’t even sell it.”

A young Edgar T. Scott, an investment banker, and his family at Chiltern, the family's “summer palace.”

There was Mansfield, a southern plantation near Georgetown, South Carolina, that belonged to the Montgomery side of the family. That was later unloaded to “an engineer who’d helped design the interstate highway system,” she writes. When she visited decades later, it was in a state of “Southern Gothic rot.”

And then there was Ardrossan, the gem that at one point counted more than 60 outbuildings, including stables, cottages, and gatehouses, most inhabited by relatives. For a deep-dive on its architectural history, there is historian David Nelson Wren’s Ardrossan: The Last Great Estate on the Philadelphia Main Line , a rich and exhaustively researched illustrated book published in 2017 by Bauer and Dean. But to understand the place’s resilience, Scott turned to kith and kin who, at one time or another, had called it home.

Members of the Montgomery Scott clan riding into the motor court at Ardrossan.

“In my father’s generation, there were powerful inducements to settle on Ardrossan,” she writes. “It was a full-service, cradle-to-grave operation. In return for living there, a descendant of the colonel would have not only a house but a place in a web of colorful clansmen and retainers.” During holiday dinners in the Big House, “a few fractious, fourth-generation, undergraduate cousins might be thinking dark thoughts about cultural hegemony, Thorstein Veblen, and social stratification. But most of those in attendance believed down deep that they were the beneficiaries of something rare and worth preserving.” And so they did, until they couldn’t anymore.

In the years since Scott’s father died, in 2005, many of the old cow fields and horse pastures have been carved into residential lots. “And if the current plans of development are carried out, all the land except 15 acres around the Big House will be subdivided,” she says, somewhat forlornly.

What will happen to Colonel Montgomery’s ambitious, impractical manse “is still up in the air,” she adds. “But weren’t we lucky to keep it all intact for so long.”

Dana Thomas is the author of Fashionopolis: The Price of Fast Fashion and the Future of Clothes, to be published by Penguin Press in September.