When it comes to destinations with an impressive architectural history, your first, second, or perhaps even your fifth thought might not be New York’s Long Island, but you’d be mistaken not to include it on your list. The architecture of the region dates back several centuries, from the days of Dutch and British colonial rule to America’s formative years to the development of the contemporary enclaves in the Hamptons today. Designer Kyle Marshall, creative director of Bunny Williams Home, has done a deep dive into Long Island residential architecture in his new book, Americana: Farmhouses and Manors of Long Island ( Schiffer Publishing, $40 ), available online and in independent bookstores next month. We spoke to Marshall about his connection to Long Island, his research process, and what he intends to write next.

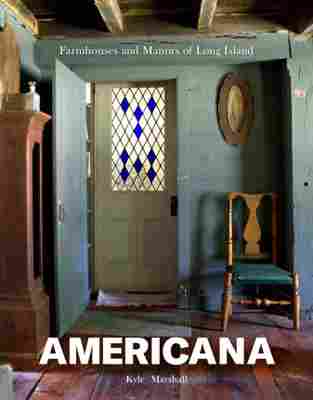

Americana: Farmhouses and Manors of Long Island by Kyle Marshall.

Architectural Digest : What draws you to the aesthetic of Long Island farmhouse and manor architecture?

Kyle Marshall : I’m drawn to the atmosphere of these houses—old homesteads, farmhouses, and manors—because they possess an understated confidence that is deeply alluring. Many are highly personal. All are the result of a narrative of centuries of evolutionary growth: Dutch and English colonial origins, layers of designed accretions by the generations, occasional subtractions, further renovations and revisions. It’s another dormer here, a porch or wing there, two settees and five candles, and you’re almost there.

Rock Hall in Lawrence.

AD : What inspired you to write the book?

KM : In part due to the island’s connection with New York City, a distinct “Long Island farmhouse” look was documented—really, framed—and occasionally disseminated by certain magazines during the 20th century, a look of rambling but smart old houses in a salty-marsh-air atmosphere. I’ve always found that charming. But there was very little information regarding how the fantasy was realized, and of the histories behind the fantasies. So that, combined with having grown up on the island’s North Shore, formed an initial, searching backbone to the project.

When I recognized there was a gap in the library on the subject—Harold Donald Eberlein’s 1928 volume was probably the last proper book to touch on the subject, and that predates the magic of most of the 20th and the 21st century—and after we bought a small house related to the type, I decided to give the project a proper go.

Sagtikos Manor in West Bay Shore.

AD : What was your research process like?

KM : My visits by foot, bike, boat, car or, in one case, subway, to the houses, to photograph them and chat with their stewards, either owners or caretakers, formed the basis of research. I also used the collections of local historical societies and libraries, several university libraries, New York City’s public library, and the Library of Congress. I had already formed a decent collection of books, pamphlets, magazines, and other printed matter related to the subject, and so, fortunately, I had those at hand, too.

I selected properties that illuminate the range of the subject, so it’s a banquet of examples, not an exhaustive survey. Also, the houses, whether privately owned or managed as a museum, had to feel alive, had to have a point of view, to avoid that sense of nostalgia that can pervade the presentation of design connected with the past. But all design is connected with the past, so that’s not the only way. So here everything was shot with daylight, so readers could have a sense of what it feels like to walk, or sit and drink and eat and gossip, in the rooms.

Thatch Meadow Farm in Head of the Harbor.

AD : Do you find that this Long Island style permeates your work as a designer?

KM : I think their evolutionary sensibility does, in that design fantasies and design histories are codependent records—which came first, so to speak. And so does the sense that references should be, ideally, incorporated in a subtle rather than overt way. Subtle references anchor design to history, a greater context, in a reassuring manner, but overt references run the risk of being cool only to be shortly jettisoned as unfashionable by the next generation, a decade or week later.

Good design isn’t expendable or easy to part with. In terms of object and furniture design, I always think, would someone want to buy this in 50 years? Would a future grandchild bring this to their own house? It’s a question of quality and of being green. The oldest of the houses featured have managed to find sympathetic owners over the course of several centuries, certainly a testament to their positive attributes and potential as theaters for everyday life.

Point Place in Miller Place.

AD : What do you hope readers will take away from the book?

KM : I hope people feel they were able to glimpse the atmospheres of these special houses, that moment of intrigue and, ideally, some satisfaction or inspiration, particularly in regard to the art of stewardship, a sub-art of living well.

AD : Will you write more books?

KM : Ah, yes, a few ideas are brewing, about people living in these atmospheres…