The traditionally low-density capital of Ecuador, declared a UNESCO World Cultural Heritage Site in 1978 for its well-preserved historic center, is quickly becoming a crane city. And those cranes are building towers by some of the world's top architects: Pritzker Prize winner and AD100 Hall of Famer Jean Nouvel , AD100 Bjarke Ingels , Moshe Safdie , and Carlos Zapata all have projects currently under construction in Quito, where the population of nearly 2 million sprawls over an area of approximately 145 square miles.

Though this concentration of global talents engaged in designing for the city might indicate otherwise, the phenomenon is entirely new. Towers have dotted the bustling downtown—where architectural styles range from Latin American modernism to brutalism to 1930s Czech-influenced to contemporary prefab—since the 1970s, but the first starchitect-designed structure rose only in 2017. Initiated by an enterprising local developer and fueled by a revised zoning code and new transit-oriented development incentives, Quito is shaping up to be a starchitect’s next frontier.

With new transit-oriented development incentives along the 2020 metro, luxury residential towers are rising in Quito, particularly at the edges of La Carolina Park. One of the latest is a pink-tinted tower complex by BIG, where the permeable ground level is activated with retail and office space.

The urban shift in Quito started with a relocation. In February 2013, the municipal government moved the entirety of Quito’s 1960 Mariscal Sucre International Airport from the dense residential and commercial neighborhood that had grown around it to an agricultural area 12 miles away. The previous location of the airport (now being transformed into a large park) had capped surrounding building heights at four stories. A revised zoning code now allows towers in the city up to 40 stories, though air rights must be purchased from the government.

Recognizing the new potential to build taller and better, Quito-based development company Uribe & Schwarzkopf has been recruiting world famous architects with a "why not here?" attitude. For the 46-year-old, two-generation company where father Tommy Schwarzkopf and son Joseph Schwarzkopf work side by side, it became increasingly obvious that sometimes you can't do it all. For about the last 40 years, the firm had taken a design-build approach, with Tommy (a trained architect) at the helm of designing modular residential and commercial towers across the capital. The buildings are efficient, but far from radical, on a growing skyline. When Joseph came into the family company, the two hypothesized that starchitects could bring more intrigue to their projects, and Tommy says he was satisfied to hand over the design reins and accept a new development challenge.

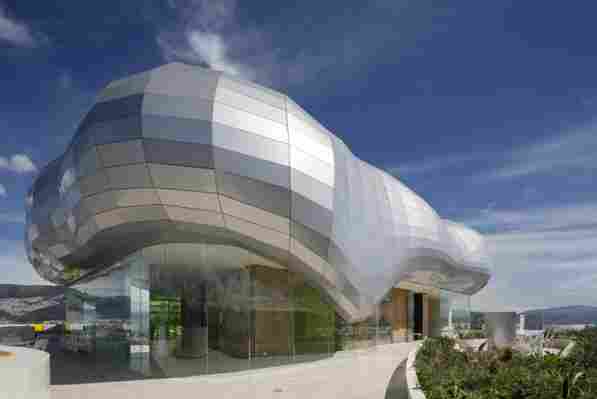

The roof of Yoo Quito by Arquitectonica and Philippe Starck has been designed as an amenities level for residents.

Thus, their firm’s first foreigner-designed tower sprung up in González Suárez, an artsy, bohemian, and increasingly affluent neighborhood on a slope. The developers called on Miami-based Arquitectonica to design the 22-story residential Yoo Quito. French designer Philippe Starck crafted the interiors and amenities, which are dotted with his furniture and inspired by the clouds the tower seems to touch. Floating above the roof terrace is a cloudlike shape of undulating aluminum panels that hides the building’s necessary mechanical systems. On the ground level, too, the tower does something new for Quito: Retail at the base engages the public with the building in a city where most private residences have a barrier to entry.

A rendering of the pool atop the IQON tower by BIG—Bjarke Ingels Group.

At the moment, Quito suffers from a pedestrian-unfriendly urban streetscape. At 9,350 feet, the city is spread out atop an Andean plateau just beneath the Pichincha volcano; its newest suburbs, Cumbayá and Tumbaco, spill over into the eastern valley. Car culture is king for the growing middle class, and public transit can be inefficient for the large number of low-income families, many of whom reside in informal housing communities that cluster along the steep hills. For those traveling short distances, sidewalks are often uneven and underpopulated at night. Lots of those who do crowd downtown streets are refugees from neighboring Venezuela who have been seeking sanctuary in the Ecuadorian capital since 2015. Recently, the nation adopted policies that work against regularization and has not taken steps in the low-income housing sector that would indicate that it considers these migrations permanent.

BIG's first tower in Quito (and first project in Latin America) was IQON, across from La Carolina Park, with views of the volcanos Pichincha and Cotopaxi. Through-floor units allow maximum light and air in the center of the curved volume of the residential building.

The government is, however, working to increase city center density through the city's first underground metro line, whose first phase will run from north of the former airport to the southern suburbs in 2020. Explains Jacobo Herdoiza, a former secretary of territory for Quito, the hope is that upper-class residents who currently drive from the suburbs to work downtown each morning will ditch their cars for mass transit and move back to the city center. For developers, an incentive has been set in place: If you construct a new residential project within an eight-minute walk from the new metro or a five-minute walk from a bus rapid transit station, the city will pick up the tab for your air rights.

At BIG's EPIQ tower complex, the ground floor is conceived as an extension of the park across the street, a landscaped public realm for rest, play, and shopping. This kind of public plaza at the base of a residential building is a new design strategy for Quito, where most living spaces have a barrier at the streetwall.

These transit-oriented development incentives convinced Uribe & Schwarzkopf to hire one of the world's most buzzy architects, Bjarke Ingels of BIG , to design two residential towers (the firm's first projects in Latin America) along the forthcoming metro line. Across from La Carolina Park, the city's most popular green space, the 32-story IQON and the 24-story EPIQ towers by the architect are quickly rising. The former is set to be the city's tallest building and has a facade that, when trees are planted on each terrace, will reflect the adjacent park. The latter takes a more historic approach to its materials: It will be constructed of concrete dyed in various shades of pink to reflect Quito's terra-cotta heritage. Green roofs atop each setback become communal terraces for residents, while the ground level is activated with retail, offices, and a restaurant, a strategy that is hoped to encourage pedestrian traffic.

On the edge of La Carolina Park, Moshe Safdie's Qorner Tower is his first project in Ecuador. The design emphasizes indoor-outdoor living with double-height terraces and a green wall on the north facade.

Just up the street, Israeli-Canadian star Moshe Safdie of Boston-based Safdie Architects has designed Qorner Tower, a 24-floor residential building with double-height terraces that stagger its facade. A garden wall climbs the north face and photovoltaic panels offset some energy production. And on the park’s north side, New York–based Carlos Zapata has designed Unique, a sleek glass tower that will top out at 23 stories of apartments with panoramic views of the city. Residents, too, are pushing the housing market toward these amenity-driven, beautiful building designs, says Ecuadorian interior designer Adriana Hoyos. "Quito is a transitional city, but new clients are looking for a more contemporary style," she comments, noting that interiors with 360-degree views and open kitchens are where her clients' priorities lie. "These new towers are raising the bar—they are both competitive and complementary to the rest of the world's urban architecture."

In Cumbayá, architect Jean Nouvel designed a nine-building residential complex that features stone-covered facades and wood-screened apartment terraces, and emphasizes greenery. The complex, called Aquarela, was developed by Uribe & Schwarzkopf and is currently under construction.

Though Uribe & Schwarzkopf hasn’t put all their eggs in one downtown densifying basket (they’ve also tapped Jean Nouvel to design Aquarela, a jungle-like complex of nine residential buildings wrapped in greenery in suburban Cumbayá), they are banking on the appeal of these foreign architects and their striking designs to convince luxury-level residents to make the move. Tommy Schwarzkopf summed it up in a statement: “A new skyline for the city is being created and a new type of citizen is emerging.”